Jobs Model Admits It’s Guessing, Asks Magic 8-Ball To Unionize

The jobs revision arrived like a stork carrying an audit: adorable, screaming, and impossible to ignore. The nation’s birth-death model tripped over its own umbilical cord, then calmly asked if anyone else had been counting imaginary baristas. I cover business for a living, which means I translate quarterly miracles into mortal nouns and wait for gravity to file its paperwork. Today, gravity sent a memo stamped LOL.

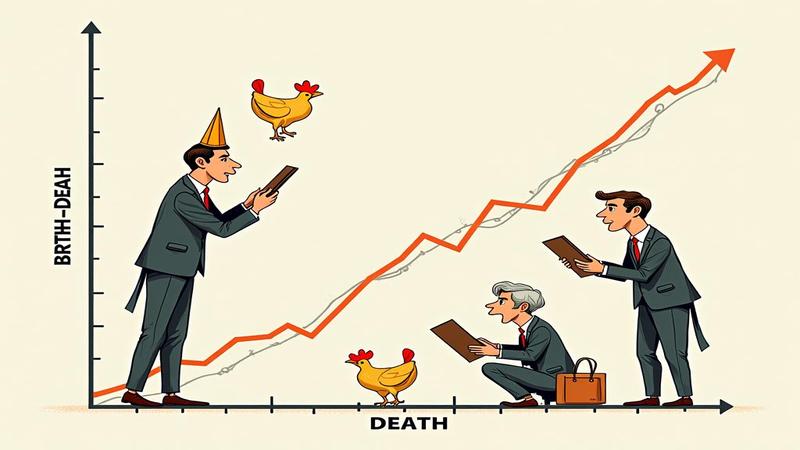

For the uninitiated, the birth-death model is how we estimate businesses that are born and businesses that die before paperwork catches up. It is a perfectly normal system if your definition of normal includes an abacus, a séance, and a coin flip that sighs. The model said jobs were thriving like sourdough starters; the revision said some of those starters were just jars of air named Kevin.

In human terms: a few hundred thousand positions were living only in the warm glow of optimism and spreadsheet conditional formatting. Picture a cupcake kiosk hiring 12, a crypto spa onboarding 30, and a pop-up ax-throwing yoga studio promoting three to Chief Mindfulness Officer, none of which survived the second rent. The model sent flowers; the revision sent the bill.

Birth-death was built for a noble purpose: to keep the numbers honest while paperwork naps. Then it started freelancing as a novelist. It doesn’t so much count jobs as hold a baby shower for a ghost and then file for dependent credits. If you’ve ever guessed a jar of jellybeans, now imagine the jellybeans have HR.

A senior estimator walked me through it using diagrams and a long exhale. ‘We model firm births using historical patterns, seasonal factors, and vibes,’ they said, carefully not elbowing the ouija board off the desk. ‘Then we subtract firm deaths, unless they’re merely mostly dead, which is statistically adorable.’ I nodded, the way one nods at a cat who has opened TurboTax.

Out in the wild, business owners navigated reality with an economist-approved dartboard. One restaurateur told me he hired eight servers because the model said his neighborhood was experiencing a fertility boom in tapas. Then he discovered the tapas baby had a shell company in Delaware and a shellfish allergy.

Politicians did what they do best: declare victory atop a trapeze labeled Maybe. One camp cheered, ‘See, jobs are fine except for the ones that never existed!’ The other shouted, ‘Aha, the economy is a hologram projected by a projector that’s on fire!’ Both sides then agreed to hold a bipartisan hearing on the correct number of clowns that can fit in a payroll car.

Markets responded with their usual serenity, which is to say they drank espresso through a foghorn. The index that tracks expectations of expectations rallied on news that the news had been wrong in a way that might now be right. Traders lit scented candles called Pro Forma and refreshed their faith in the long-run, which remains a charming myth set in a land of functioning calendars.

In search of clarity, I bought a USB desktop crystal ball. It immediately downgraded me to Neutral with a watch for stray confetti. The device told me that in Q3, all data will simply be an interpretive dance performed by bond yields in a smoke machine.

I asked several economists how to fix birth-death, and they each gave me a different recipe for naan. One proposed a Frankenstein upgrade called the Nursery-Cemetery-Couch model, which counts the newly born, the dearly departed, and the companies that still exist but live under a weighted blanket. Another floated Schrödinger’s Internship: the job exists and doesn’t until the first paycheck clears or the Slack channel goes eerily quiet.

As a compromise, I suggested we text every storefront at midnight: ‘u up? jobs alive? y/n.’ We could also triangulate from pizza box volumes, open-table hiccups, and the number of balloons slowly deflating above Main Street. If the balloon droop hits 45 degrees, we revise down; if it floats, somebody just invented a new title for cashier.

Here’s the sober bit, delivered in the tone of someone holding an abacus and a fire extinguisher: models are bridges over fog, not destinations. We need them until we don’t, and then we need better ones. Until that arrives, I’ll do what I always do: follow incentives, raise one eyebrow at serial miracles, and keep a towel for when the data spits.

So yes, the birth-death model needs a fix, preferably one that doesn’t involve interpretive astrology or payroll necromancy. In the meantime, please join me at the nation’s newest labor bureau: the Maternity and Obituary Desk, where we deliver congratulations, condolences, and a single calculator that only displays the word ‘Depends.’